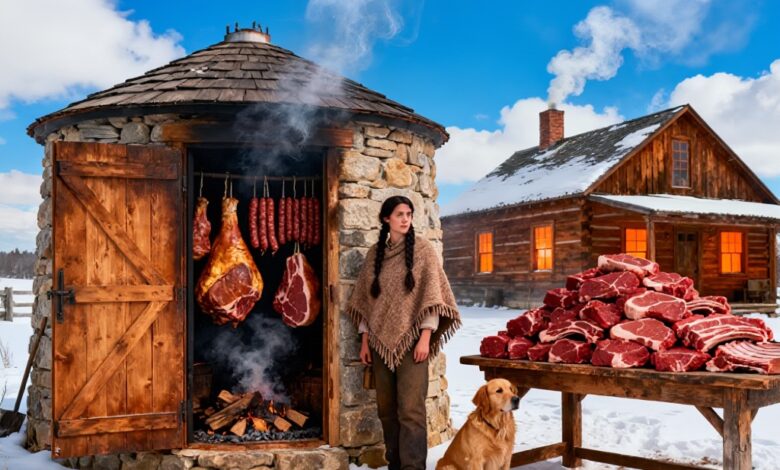

The Meat Tower They Ridiculed Became a Survival Lifeline!

In the rolling pastoral landscape of Greene County, Missouri, tradition usually dictates the rhythm of farmhouse life. So, when Martha Callahan began stacking an unusual vertical series of wooden crates behind her barn in the autumn of 2025, the local community took notice. At fifty-eight, Martha was a woman of quiet iron, widowed two years prior and left to manage a farm that had once been the domain of her husband, Ray. Ray had been the master of the smokehouse, a man who understood the alchemy of salt and hickory. After his passing, a brutal winter storm and a subsequent freezer failure resulted in the loss of half a hog—a devastating blow to Martha’s food security and her spirit.

The loss sparked a transformation. Refusing to remain vulnerable to the whims of an aging electrical grid and rising grocery costs, Martha retreated into a period of intense study. She bypassed modern appliance catalogs and instead immersed herself in the forgotten wisdom of Appalachian curing, Scandinavian drying techniques, and Civil War-era journals. Her research culminated in the construction of a twelve-foot-tall wooden structure that the neighbors quickly dubbed the “Meat Tower” or, less charitably, the “Lighthouse for Pigs.”

The structure was a masterclass in passive engineering. It featured a square base that tapered slightly toward the top, constructed from wooden slats spaced with mathematical precision to facilitate airflow. At the pinnacle sat a small metal turbine that spun even in the slightest breeze. To the casual observer, it was an eyesore; to Martha, it was a vertical convection chamber. The design utilized the Stack Effect: cool air entered through mesh-protected lower vents, while warmer, moisture-laden air rose through the tiered racks and exited through the spinning turbine. By increasing the height of the chamber, Martha increased the draft, ensuring that the air around her hanging pork bellies was never stagnant—the primary enemy of meat preservation.

In late October, as the Missouri air turned crisp, Martha introduced her first batch of acorn-fed pork. She salted the slabs with a generous hand, seasoned them with coarse black pepper and brown sugar, and suspended them within the tower’s upper reaches. Neighbors like Earl Jenkins watched with skepticism, predicting that the local raccoons would have a feast or that the humid Missouri “Indian Summer” would turn the meat to mold before Thanksgiving. Martha, however, had fortified her tower with fine steel mesh and a base of concrete blocks to deter predators. More importantly, she monitored the internal microclimate with a hygrometer and thermometer, trusting the physics of her design.

As November gave way to a biting December, the “Meat Tower” began to prove its worth. While the humidity in the region fluctuated, the constant airflow within the tower allowed moisture to evaporate from the meat slowly and evenly. By the time an ice storm paralyzed Greene County in January, the town was plunged into a dark, frozen chaos. Power lines snapped under the weight of the ice, and the hum of freezers across the county died out. Earl Jenkins lost three deer roasts; the rest of the neighborhood scrambled to salvage thawing ground beef and poultry.

During the blackout, Martha walked to her tower with a lantern. Amidst the silence of the frozen farm, the turbine spun lazily. Inside, the bacon hung in a state of perfect stasis. Without a single watt of electricity, the natural cooling and drying process continued unabated. When the power finally flickered back on four days later, the neighborhood was reeling from significant food losses, but Martha’s stores were untouched. The laughter that had greeted her construction in October was replaced by a thoughtful, mounting curiosity.

By February, Martha’s bacon had transitioned from a local joke to a survival legend. When she finally invited the neighborhood over in the spring, the experience was transformative. The aroma of dry-cured bacon, fried in a seasoned cast-iron skillet and served over warm biscuits, drifted across the fields. The flavor was a revelation—rich, concentrated, and free from the watery brine of mass-produced supermarket varieties. Earl Jenkins, taking his first bite, finally understood that this wasn’t just a quirky project; it was a reclamation of autonomy.

The true miracle of “Martha’s Tower” was its longevity. As the Missouri sun intensified through May and June, the bacon remained safe and delicious. By July, when most households were stretching their budgets to accommodate soaring meat prices, Martha still had a surplus of high-quality protein. She explained to the skeptics that before the advent of the domestic refrigerator, food preservation was a matter of managing biology and physics. Her tower was a return to those roots, proving that moisture control was far more critical than refrigeration for certain types of protein.

The “Meat Tower” eventually became a catalyst for community resilience. By the fall of 2026, several smaller versions of the tower began appearing in backyards across Greene County. The local hardware store reported a surge in sales for steel mesh and adjustable vents. Martha, ever humble, shared her design sketches freely, viewing the dissemination of knowledge as a way to honor Ray’s memory and strengthen her neighbors. Her bacon eventually won first place at the county fair, with judges praising the balance of its cure and the integrity of its texture.

Martha’s story serves as a poignant reminder that innovation often involves looking backward as much as forward. In an era where modern conveniences can fail in a single storm, there is profound security in simple, low-tech solutions rooted in historical success. The tower was never just about bacon; it was about the peace of mind that comes from knowing that one’s survival is not tethered to a fragile wire. As Martha sat on her porch in the humid Missouri summer, watching the tower’s turbine spin, she knew she had built more than a smokehouse. She had built a monument to self-reliance, proving that with enough grit and a little bit of wind, one can endure even the hardest of seasons.